Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

| Antoine de Saint-Exupéry | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Antoine de Saint Exupéry 29 June 1900 Lyon, France |

| Died | 31 July 1944 (aged 44) Offshore, south of Marseille, France |

| Occupation | Aviator, Writer |

| Nationality | French |

| Period | 1929-1948 (posthumous) |

| Genres | Autobiography, Belles-Lettres, Children's Literature |

| Spouse(s) | Consuelo Gómez Carillo de Saint-Exupéry, (1931-death) |

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry[1] (French pronunciation: [ɑ̃twan də sɛ̃tɛɡzypeˈʁi]) (29 June 1900—31 July 1944) was a French writer and aviator. He is best remembered for his novella The Little Prince (Le Petit Prince), and for his books about aviation adventures, including Night Flight and Wind, Sand and Stars.

He was a successful commercial pilot before World War II, joining the Armée de l'Air (French Air Force) on the outbreak of war, flying reconnaissance missions until the armistice with Germany. Following a spell of writing in the United States, he joined the Free French Forces. He disappeared on a reconnaissance flight over the Mediterranean in July 1944.

Contents |

Early years

Antoine Jean-Baptiste Marie Roger de Saint Exupéry[2] was born in Lyon to an old family of provincial nobility, the third of five children of Marie de Fonscolombe and Viscount Jean de Saint Exupéry, an insurance broker who died before his son was even four.

After failing his final exams at preparatory school, Saint-Exupéry entered the École des Beaux-Arts to study architecture. In 1921, he began his military service with the 2e Régiment de chasseurs à cheval (English: 2nd Regiment of Light Cavalry). He was then sent to Strasbourg for training as a pilot. The following year, he obtained his license and was offered transfer to the air force. Bowing to the objections of the family of his fiancée—the future novelist Louise Leveque de Vilmorin—he instead settled in Paris and took an office job. The couple ultimately broke off the engagement, however, and he worked at several jobs over the next few years without success.

By 1926, Saint-Exupéry was flying again. He became one of the pioneers of international postal flight, in the days when aircraft had few instruments. Later he complained that those who flew the more advanced aircraft had become more like accountants than pilots. He worked on the Aéropostale between Toulouse and Dakar, and became the airline stopover manager in Cape Juby airfield, in the Spanish zone of South Morocco, inside the Sahara desert. In 1929, Saint-Exupéry moved to Argentina, where he was appointed director of the Aeroposta Argentina Company. This period of his life is briefly explored in Wings of Courage, an IMAX film by French director Jean-Jacques Annaud.

Writing career

Saint-Exupéry's first story, "L'Aviateur" ("The Aviator"), was published in the magazine Le Navire d'Argent. In 1929, he published his first book, Courrier Sud (Southern Mail); his career as aviator was also burgeoning, and that same year he flew the Casablanca/Dakar route.

In 1931, Vol de Nuit (Night Flight) —the first of his major works and winner of the Prix Femina—was published and made his name. It covers his experiences with the Aéropostale. That same year, at Grasse, Saint-Exupéry married Consuelo Suncin (née Suncín Sandoval), a widowed Salvadoran writer and artist. It would be a stormy union, as Saint-Exupéry traveled frequently and indulged in numerous affairs, most notably with the Frenchwoman Hélène (Nelly) de Vogüé. De Vogüé became Saint-Exupéry's literary executrix after his death, and also wrote a Saint-Exupéry biography under the pseudonym Pierre Chevrier.

Desert crash

On 30 December 1935 at 14:45 after a flight of 19 hours and 38 minutes Saint-Exupéry, along with his navigator, André Prévot, crashed in the Libyan Sahara desert en route to Saigon. Their plane was a Caudron C-630 Simoun n°7042 (Registration F-ANRY). The crash site may be the Wadi Natrun. The team was attempting to fly from Paris to Saigon faster than any previous aviators, for a prize of 150,000 francs. Both survived the landing, but were faced with the prospect of rapid dehydration in the Sahara. They had no idea of their location. According to his memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, their sole supplies were grapes, two oranges, and a small ration of wine. What Saint-Exupéry himself told the press shortly after rescue was that the men only had a thermos of sweet coffee, chocolate, and a handful of crackers,[3] enough to sustain them for one day. They experienced visual and auditory hallucinations; by the third day, they were so dehydrated they ceased to sweat. Finally, on the fourth day, a Bedouin on a camel discovered them, saving their lives. Saint-Exupéry's fable The Little Prince, which begins with a pilot being marooned in the desert, is in part a reference to this experience.

American sojourn and The Little Prince

Saint-Exupéry continued to write and fly until the beginning of World War II. During the war, he initially flew a Bloch MB.170 with the GR II/33 reconnaissance squadron of the Armée de l'Air. After France's 1940 armistice with Germany, he traveled to the United States. The Saint-Exupérys lived in a penthouse apartment at 240 Central Park South[4] in New York City and a rented mansion (The Bevin House) in Asharoken[5] on Long Island's north shore between January 1941 and April 1943. They also resided in Quebec City in Canada for a time in 1942.[6][7] He wrote The Little Prince in Asharoken in mid-to-late 1942; the manuscript was completed by October.[8]

Disappearance

Following his nearly twenty-five months in North America, Saint-Exupéry returned to Europe to fly with the Free French Forces and fight with the Allies in a Mediterranean-based squadron. Then 43, he was older than most men assigned such duties; he also suffered pain, due to his many fractures. He was assigned with a number of other pilots to P-38 Lightnings, which an officer described as "war-weary, non-airworthy craft."[9] After wrecking a P-38 through engine failure on his second mission, he was grounded for eight months, but was then reinstated to flight duty on the personal intervention of General Eisenhower. Charles de Gaulle implied publicly that Saint-Exupéry was supporting Germany; depressed at this, the pilot began to drink heavily.[10]

Saint-Exupéry's final assignment was to collect intelligence on German troop movements in and around the Rhone Valley preceding the Allied invasion of southern France. On the evening of 31 July 1944, he left from an airbase on Corsica, and did not return. A woman reported having watched a plane crash around noon of August the first near the Bay of Carqueiranne off Toulon. An unidentifiable body wearing French colors was found several days later east of the Islands of Frioul south of Marseille and buried in Carqueiranne that September.

Discovery at sea

In 1998, a fisherman named Jean-Claude Bianco found, east of Riou Island, south of Marseille, a silver identity bracelet bearing the names of Saint-Exupéry and his wife Consuelo[11] and his publishers, Reynal & Hitchcock, hooked to a piece of fabric, presumably from his flight suit.

In 2000, a diver named Luc Vanrell found a P-38 Lightning crashed in the seabed off the coast of Marseille, near where the bracelet was found. The remains of the aircraft were recovered in October 2003.[11] On 7 April 2004, investigators from the French Underwater Archaeological Department confirmed that the plane was, indeed, Saint-Exupéry's F-5B reconnaissance variant. No marks or holes attributable to gunfire were found, however this was not considered significant as only a small portion of the aircraft was recovered.[12] In June 2004, the fragments were given to the Museum of Air and Space in Le Bourget.[13]

The location of the crash site and the bracelet are less than 80 km by sea from where the unidentified French soldier was found in Carqueiranne, and it remains plausible, but has not been confirmed, that the body was carried there by ocean currents after the crash over the course of several days.

Speculations in March 2008

In March 2008, a former Luftwaffe pilot, 85-year-old Horst Rippert (the brother of the singer Ivan Rebroff), told La Provence, a Marseille newspaper, that he engaged and downed a P-38 Lightning on 31 July 1944 in the area where Saint-Exupéry's plane was found.[13][14][15] According to Rippert, he was on a reconnaissance mission over the Mediterranean sea when he saw a P-38 with a French emblem behind him near Toulon.[16] Rippert says he opened fire at the P-38, which crashed into the sea.

After the war, Horst Rippert became a television journalist and led the ZDF sports department. Rippert says he came to believe that he had probably shot down Saint-Exupéry, a writer Rippert knew of because he had read his books during his youth — and also says Saint-Exupéry was one of his favorite authors.[16][17] Rippert has written a forthcoming book discussing the alleged Saint-Exupéry shootdown.[16]

The story is unverifiable, and has met with criticism from some German and French investigators.[18][19]

Contemporary archival sources, including intercepted Luftwaffe signals, strongly suggest[20] that Saint-Exupéry was not shot down by a German aircraft. An American Lightning was shot down on 30 July by Feldwebel Guth of 3./Jagdgruppe 200, the unit in which Rippert was serving. Guth’s victory claim is recorded in the lists held by the German Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv. The progress of the interception was followed by Allied radar and radio monitoring stations and documented in Missing Air Crew Report 7339 on the loss of Second Lieutenant Gene C. Meredith of the 23rd Photographic Squadron/5th Reconnaissance Group.[21]. The Mediterranean Allied Air Forces Signals Intelligence Report for 30 July records that "an Allied reconnaissance aircraft was claimed shot down at 1115 [GMT]".

By contrast, there is no claim on file from Rippert for a Lightning on 31 July and the RAF’s No. 276 Wing (Signals Intelligence) Operations Record Book notes only: "... three enemy fighter sections between 0758/0929 hours operating in reaction to Allied fighters over Cannes, Toulon and the area to the North. No contacts. Patrol activity north of Toulon reported between 1410/1425 hours".[22]

Honours

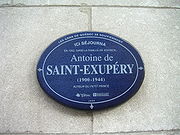

- Saint-Exupéry is commemorated by a plaque in the Parisian Panthéon.

- Until the euro was introduced in 2002, his image and his drawing of the Little Prince appeared on France's 50-franc note.

- In 2000, the Lyon Satolas Airport was renamed Lyon-Saint-Exupéry Airport in his honour.

- There is a monument for him in Tarfaya, Morocco.

- Asteroid 2578 Saint-Exupéry

Literary works

While not precisely autobiographical, much of Saint-Exupéry's work is inspired by his experiences as a pilot. One exception is The Little Prince, a poetic self-illustrated tale in which a pilot stranded in the desert meets a young prince from a tiny asteroid. The Little Prince is a philosophical story, including societal criticism and remarking on the strangeness of the adult world.

- L'Aviateur (1926)

- Courrier Sud (1929) (translated into English as Southern Mail)

- Vol de Nuit (1931) (Night Flight)

- Terre des Hommes (1939) (Wind, Sand and Stars) - Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

- Pilote de Guerre (1942) (Flight to Arras)

- Le Petit Prince (1943) (The Little Prince)

- Lettre à un Otage (1944) (Letter to a Hostage)

- Citadelle (1948) (The Wisdom of the Sands), posthumous, ISBN 978-0-226-73372-2

- Lettres de jeunesse (1953), posthumous

- Carnets (1953), posthumous

- Lettres à sa mère (1955), posthumous

- Écrits de guerre (1982) (Wartime Writings 1939-1944), posthumous

- Manon, danseuse (2007), posthumous

- Lettres à l'inconnue (2008), posthumous

Popular culture

Literature

- After his disappearance, Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry wrote The Tale of the Rose, which was published in 2000.

- Saint-Exupéry is mentioned in Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff: "A saint in short, true to his name, flying up here at the right hand of God. The good Saint-Ex! And he was not the only one. He was merely the one who put it into words most beautifully and anointed himself before the altar of the right stuff."

- In 2000, Jean-Pierre de Villers wrote a novella telling the imagined story of Saint-Exupéry's last flight, The Last Flight of the Little Prince.[23]

- Comic-book author Hugo Pratt imagined the fantastic story of Saint-Exupéry's last flight in Saint-Exupéry : le dernier vol (1994).

- His 1939 book Terre des hommes was the inspiration for the theme of Expo 67 in Montreal, also translated into English as "Man and His World".

Film

- Saint-Exupéry and Consuelo were portrayed by Bruno Ganz and Miranda Richardson in the 1997 movie Saint-Ex.

Notes

- ↑ All his books were published under the name with a hyphen which makes it his pseudonym. Memorial plaques, the 50-Franc banknote, and the bracelet he was wearing at the time of his death also show the hyphen. French Wikipédia uses the spelling Saint-Exupéry.

- ↑ According to French legal documents and his birth certificate, no hyphen is used in his name, thus written de Saint Exupéry, not Saint-Exupéry. The Armorial de l'ANF, which lists the French nobility, mentions the Saint Exupéry (de) family without a hyphen.

- ↑ Schiff, Stacy. Saint-Exupéry: A Biography. New York: 1994, A.A. Knopf. p. 258

- ↑ Jennifer Dunning (May 12, 1989). "In the Footsteps of Saint-Exupery". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DE3DA143DF931A25756C0A96F948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=2.

- ↑ Cotsalas, Valerie (2000-09-10). "'The Little Prince': Born in Asharoken". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E03E7D61739F933A2575AC0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ Schiff, Stacy (2006). Saint-Exupéry: A Biography. Macmillan. pp. page 379 of 529. ISBN 0805079130.

- ↑ Brown, Hannibal. "The Country Where the Stones Fly" (documentary research). Visions of a Little Prince. http://habpro.tripod.com/visionslp/id13.html. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- ↑ Schiff, Stacy (February 7, 2006). Saint-Exupery. Owl Books. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-8050-7913-5. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0805079130&id=h-gk5R0OmI0C&pg=PA379&lpg=PA379&dq=%22Bevin+House%22&sig=4p8_dhvcRABg-EiedAuar4UM5PU.

- ↑ Cate, Curtis, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: His Life and Times, Longmans Canada Limited, 1970.

- ↑ Buckley, Martin (7 August 2004). "Mysterious wartime death of French novelist". BBC News, World Edition (BBC). http://www.thewe.cc/contents/more/archive2004/august/antoine_de_saint-exupery_death.htm. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Saint-Exupery committed suicide says diver who found plane wreckage, published by the Cyber Diver News Network, 7 August 2004.

- ↑ "''Riou island's F-5B Lightning, Rhône's delta, France. Pilot: Commander Antoine de Saint-Exupéry''". Aero-relic.org. http://www.aero-relic.org/English/F-5B_42-68223_St_Exupery/e-00-stexuperyf5b.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry aurait été abattu par un pilote allemand, March 15, 2008 report in Le Monde newspaper in French.

- ↑ Wartime author mystery 'solved' report shown at the BBC News site on Monday, 17 March 2008

- ↑ [1] NY Times, "Clues to the Mystery of a Writer Pilot Who Disappeared", April 11, 2008

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Ivan Rebroffs Bruder schoss Saint-Exupéry ab March 15, 2008 Agence France-Presse report in German.

- ↑ German Pilot Fears He Killed Writer St. Exupéry, 16 March 2008 Reuters news story quoting Rippert in Le Figaro newspaper. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ↑ Georg Bönisch, Romain Leick, "Gelassen in den Tod" Der Spiegel, No. 13, 22. March 2008

- ↑ Jürg Altweg, "Aus Erfahrung skeptisch: Französische Zweifel an Saint-Exuperys Abschuss durch Horst Rippert", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 28, 2008, No. 32, S. 44

- ↑ Nick Beale, "Saint-Ex a péry Entre mythe et réalité." on aero JOURNAL, 2008, No. 4, pp. 78 - 81. More precise on the web-site "Ghost Bombers"(see External links)

- ↑ Lt Meredith's remains were not recovered; he is listed on the Tablets of the Missing on the Florence Italy ABMC Cemetery {ABMC Records}

- ↑ Archive sources for Luftwaffe activity over Southern France on 30 and 31 July 1944 are cited in an extensive article on the Ghost Bombers aviation history website [2]

- ↑ Jean-Pierre de Villers (2000-11-02). The Last Flight of the Little Prince. Les Editions du Vermillon. ISBN 1895873835. http://www.amazon.com/dp/1895873835.

References

- Stacy Schiff (1994). Saint-Exupéry: A Biography. Pimlico.

- "From The Murky Depths", by Benjamin Ivry in the Wall Street Journal, April 15, 2004.

External links

- Official website - (French)

- A website dedicated to the Centennial Anniversary of Antoinne and Consuelo de Saint Exupery

- Summary of the book "The little prince" (Italian)

- Another website about Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (French)

- Works by Saint-Exupéry (public domain in Canada)

- The Luftwaffe and Saint-Exupéry: the evidence (in the website "Ghost Bombers")

- Antoine Marie de Saint-Exupéry: A Frenchman of Noble and Timeless Values

- Google celebrated Antoine de Saint-Exupery's 110th Birthday with special logotype